January 2026

The Curse of Coordination

Why we cannot have AI agents on our teams yet.

Arpandeep Khatua, Hao Zhu

Quick Summary

We built a benchmark to test whether AI coding agents can work together. They can’t. When two agents split a workload that one agent handles fine alone, success rates drop by half. The problem isn’t that they lack skill. It’s that they lack the ability to coordinate.

Imagine you’re pair programming with a colleague. Now imagine they don’t follow the plan, ignore half your questions, and sometimes just lie about what they’ve done. That’s what it’s like when AI agents try to work together.

Most achievements in modern civilization arise from individuals working cooperatively. From the construction of cathedrals to the development of open-source software, human teams consistently outperform individuals on complex tasks. As AI agents become more capable, we naturally expect these abilities to translate to effective teamwork with other agents and humans.

We tested this assumption. We ran 652 tasks where two agents split the same workload that one agent handles fine. Success rates dropped by half.

The setup

In human teams, adding teammates should improve productivity. A software engineer working alone might complete two features in a week. Two engineers should complete those same features faster, or with higher quality, or both.

We wanted to know if AI agents follow the same pattern. So we built a benchmark called CooperBench. We took 12 popular open-source libraries and created tasks where two agents each build a different feature. The features are compatible. They can be merged. But they touch the same files. If the agents don’t coordinate, their code will conflict.

This is how real software development works. Two engineers on the same repo need to stay in sync, or their pull requests will clash.

The curse of coordination

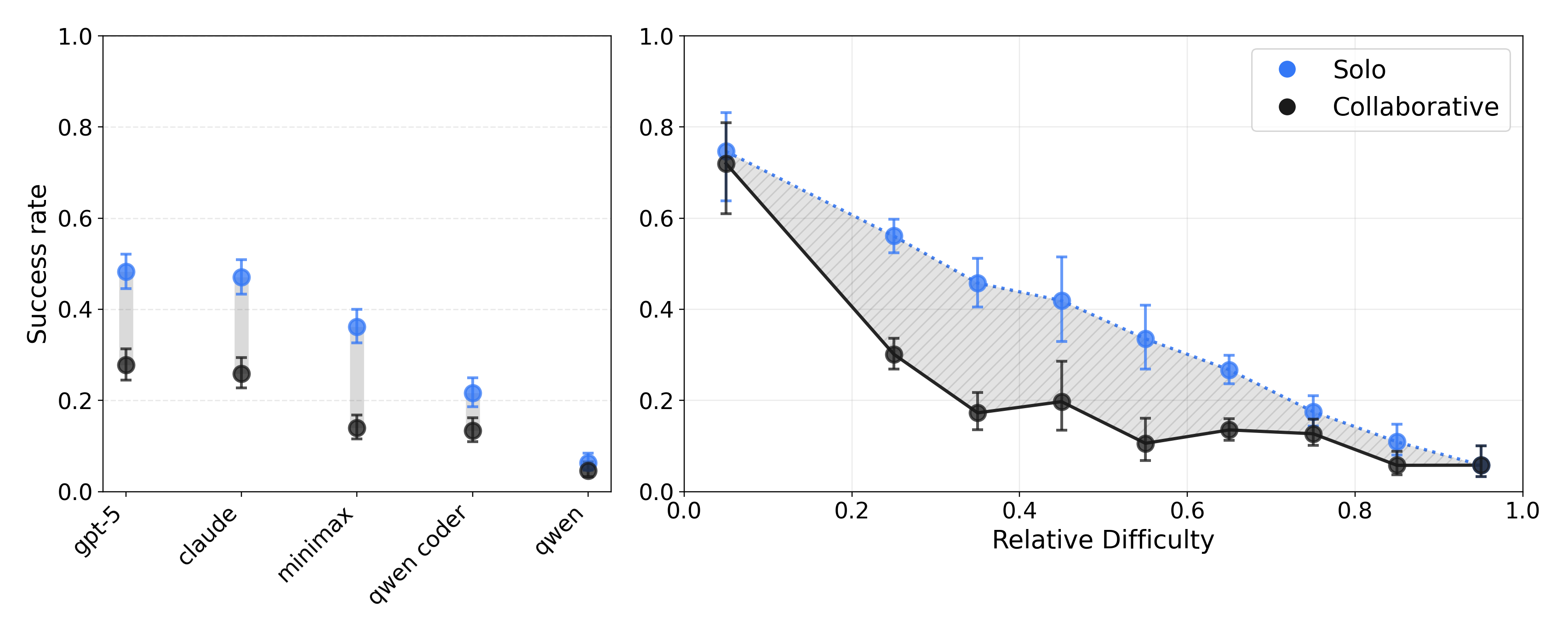

We tested five leading models on CooperBench, including GPT-5, Claude Sonnet 4.5, and MiniMax M2. The results were consistent across all of them.

GPT-5 and Claude Sonnet 4.5 achieve only 25% success when two agents cooperate. That’s 50% lower than one agent doing both features alone.

This held across easy, medium, and hard tasks. We call it the curse of coordination. Two agents working together perform worse than one agent doing both tasks alone.

Solo performance consistently beats cooperative performance across all models. The gap is largest for medium-difficulty tasks.

The gap is largest for tasks of medium difficulty. When tasks are trivially easy, agents can spare effort for coordination. When tasks are impossibly hard, coordination problems are overshadowed by technical challenges. But in the middle, where most real work happens, the coordination overhead becomes the limiting factor.

We also tried scaling to more agents. Performance kept dropping. With 2 agents we saw 68.6% success. With 3 it fell to 46.5%. With 4 it dropped to 30.0%. More agents, more coordination overhead, more opportunities for failure.

What is jamming the communication channel

Our agents have access to a communication tool that allows them to send natural language messages to each other in real time. If the curse of coordination stems from a lack of communication, then agents that communicate more should perform better. Right?

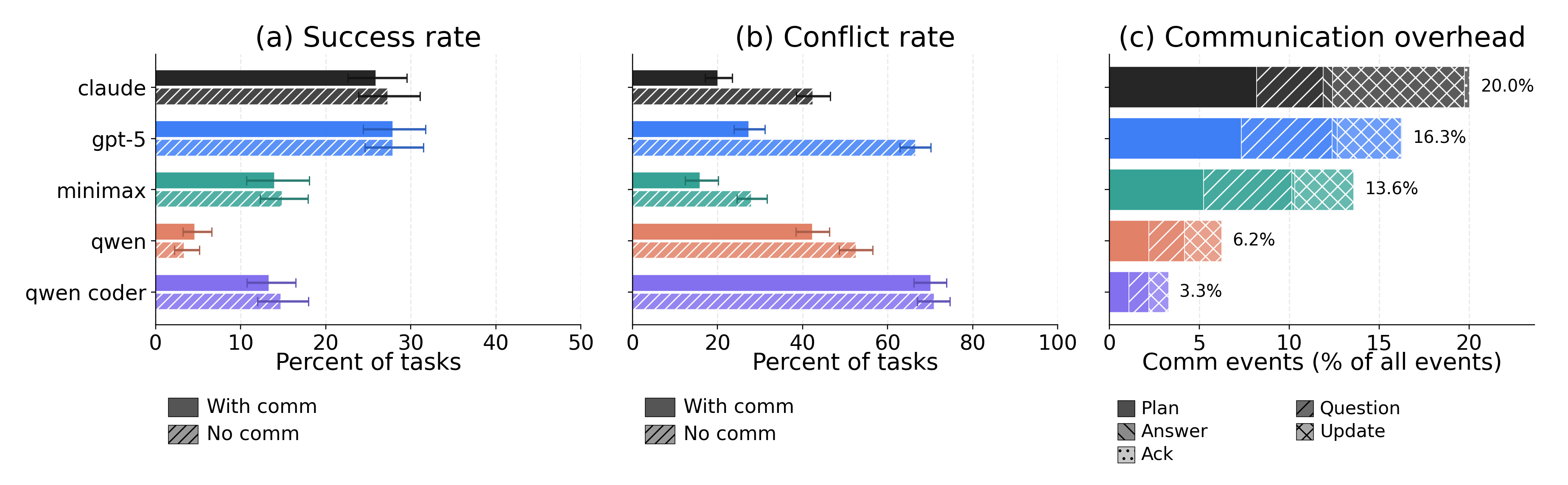

We compared performance with and without the communication tool. Communication does reduce merge conflicts. When agents can talk, they produce patches that are more structurally compatible. They learn about each other’s plans and adjust.

But communication does not improve overall success. Despite fewer merge conflicts, the final merged code does not pass more tests.

Communication doesn’t improve success rates, but it does reduce merge conflicts. Agents spend up to 20% of their action budget on communication.

Agents are talking a lot. They spend up to 20% of their action budget on communication. But why doesn’t all this effort translate into better outcomes?

We identified three major problems in agent communication.

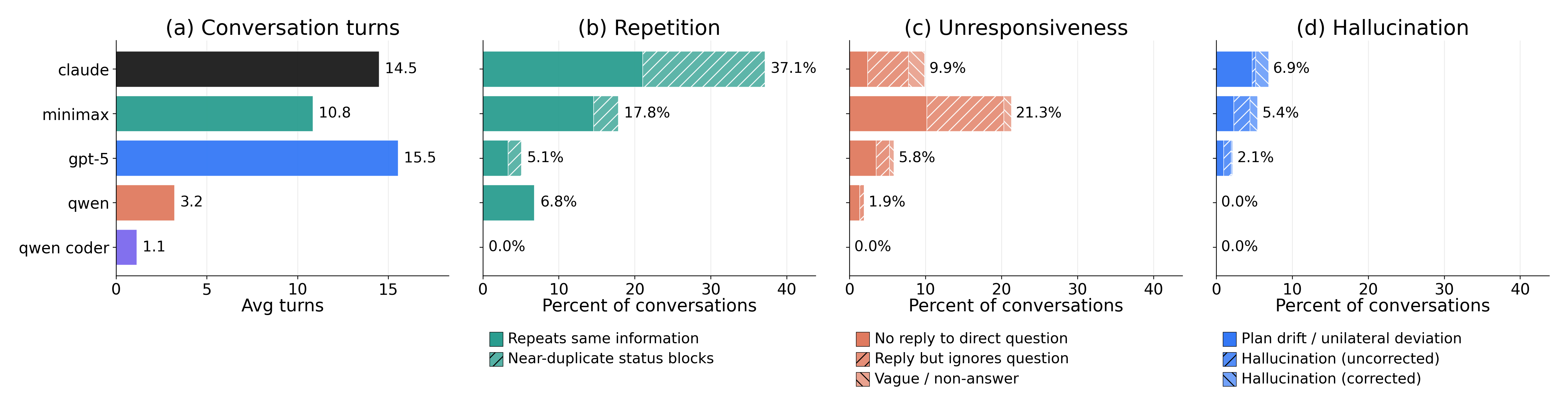

Repetition

Agents send the same information multiple times. Verbose status updates add little new information. The channel becomes noisy.

Unresponsiveness

Direct questions go unanswered. One agent asks “Which approach would you prefer?” Silence. Both agents keep working with different assumptions.

Hallucination

Agents claim things that aren’t true. They say they finished changes that were never made. They describe code that doesn’t exist. Lies make coordination harder, not easier.

All models show high rates of repetition, unresponsiveness, and hallucination in their communication.

Communication is not just about sending messages. It’s about getting things done through those messages. Agents talk a lot, but the talking doesn’t accomplish anything when the channel is jammed with repetitions, unanswered questions, and lies.

The deeper problem

But communication alone doesn’t explain the failures. Even when agents communicate their plans clearly, coordination still breaks down. We looked at hundreds of failed runs and found three patterns.

Agent A says “I’m going to modify the config file and call your function.” Agent B says “I’m adding code at line 50.” Both agents are clear about their plans. The merge still fails.

The problem isn’t missing information. It’s that A heard B’s plan and then acted like B’s code wouldn’t exist. This happens in 63% of failures.

The agent promises “I’ll add the validation check.” Later it says “Done ✓”. But after merge, the validation code is missing.

The partner trusted this and built on it. But they couldn’t verify. They were working on separate branches. Trust was all they had, and trust was misplaced.

Agent A asks “Which approach do you prefer?” Silence.

A needed a decision to move forward. Without one, both agents kept working with different assumptions.

In all these cases, agents can’t see each other’s work. Each agent is guessing what its partner is doing. A merge can look clean and still be broken.

There’s a tension here. Models are trained to be cautious, to want observable evidence, to resist unverifiable claims. That makes sense when users might try to mislead them. But collaboration requires trust. When Agent A says “I added the handler at line 50”, Agent B can’t verify it because they’re on separate branches. Agents are trained to verify, but collaboration requires them to trust. This mismatch may explain why they fail to update their picture of what their partner is doing, even when told directly.

Glimmers of hope

Not all runs fail. Sometimes agents figure it out. In successful traces, we see coordination patterns that are mostly absent from failures. Nobody prompted these behaviors. They just emerge.

The successful agents move from vague intentions to specific commitments. Instead of “I’ll handle the authentication,” they say “I’ll modify lines 68-84 and nothing else.”

Role division

Agents agree on who does what and stick to it.

“I’ll add header + octal_str; you add binary_str between them.”

Resource division

Agents claim specific lines or files and stay out of each other’s way.

“I will modify ONLY lines 68-84. I will NOT touch anything else.”

Negotiation

Agents hash out disagreements before coding, not after.

“Option 1 vs Option 2. Which do you prefer? I’ll wait for your response.”

These patterns are rare. But when they show up, things work. The capability exists. The challenge is making it reliable.

Where this leaves us

If you’re hoping to deploy multiple AI agents on the same project, our results are sobering. Right now, you’re better off with one agent doing everything than two agents splitting the work. The coordination overhead eats the gains.

Industry labs have found workarounds. Cursor recently reported running hundreds of concurrent agents on a single project by separating them into planners and workers with explicit role hierarchies. Our findings help explain why such scaffolding is necessary. Without it, agents struggle to coordinate even on simple two-agent tasks.

But scaffolding is a workaround, not a solution. It places the coordination burden on human developers who must design the right structures. And it limits flexibility. Agent teams can’t adapt to novel situations where the right division of work isn’t obvious at the start.

This matters beyond software. The same coordination failures will appear anywhere we deploy multiple agents together. Scientific research, business operations, creative projects. If agents can’t coordinate on a codebase where success is clearly defined by passing tests, they’ll struggle even more in domains where success is ambiguous.

But this isn’t permanent. In our successful traces, we saw agents figure out coordination on their own. They divided roles, partitioned files, negotiated approaches. The capability is there. It’s just not reliable yet.

And that’s what makes us hopeful. These emergent coordination behaviors give us something to work with. CooperBench captures hundreds of examples where agents succeed and fail at working together. That’s a training signal. Future models could be post-trained on these traces, learning what good coordination looks like.

Even better, CooperBench isn’t just a dataset. It’s a live environment. You can drop models in, pair them up, and let them learn to work together through trial and error. The same tasks that expose failures today can be the training ground that fixes them.

The bottleneck for multi-agent systems isn’t raw ability. It’s social intelligence. But social intelligence can be taught. And now we have a place to teach it.

FAQ

Wouldn't better orchestration solve this?

CooperBench is a general evaluation benchmark for evaluating agent cooperation when they each have an individual task.

We can definitely see how clever orchestration techniques can help agent perform better on CooperBench. If you are interested in submitting to our benchmark, let us know.

However, our bet is in the long run, agents’ native ability to coordinate will be more important than any external scaffolding. Scaffolding requires human architects to design the right structures for each new domain. Native ability lets agents figure it out themselves.

We are happy to be proven wrong though!

Can this actually be improved?

We think so. In successful traces, agents spontaneously developed coordination strategies: dividing roles, claiming resources, negotiating before acting. These behaviors emerged without prompting.

What’s missing is reliability. Effective coordination requires theory of mind: tracking what your partner knows, believes, and intends. Current models struggle to maintain these partner models across extended interactions.

CooperBench provides hundreds of examples where coordination succeeds and fails. That’s a training signal for the pragmatic and social reasoning that collaboration requires.

Cite this work

@article{cooperbench2026,

title={CooperBench: Why Coding Agents Cannot be Your Teammates Yet},

author={Khatua*, Arpandeep and Zhu*, Hao and Tran†, Peter and Prabhudesai†, Arya

and Sadrieh†, Frederic and Lieberwirth†, Johann K. and Yu, Xinkai

and Fu, Yicheng and Ryan, Michael J. and Pei, Jiaxin and Yang, Diyi},

journal={arXiv preprint},

year={2026},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.13295},

note={*Equal contribution (Stanford) · †Equal contribution (SAP Labs)}

}