January 2026 · Research

The Curse of Coordination

Why adding a teammate makes AI agents worse, not better

Arpandeep Khatua*, Hao Zhu* et al.

Stanford University & SAP Labs

Most achievements in modern civilization arise from individuals working cooperatively. From the construction of cathedrals to the development of open-source software, human teams consistently outperform individuals on complex tasks. As we deploy AI agents in collaborative settings, we naturally expect that strong individual capabilities will translate to effective coordination.

We tested this assumption.

When we assigned two agents the same workload a single agent could handle, success rates dropped by half. Adding a teammate made agents worse, not better.

The question we set out to answer

In human teams, we expect that adding teammates will improve productivity. A software engineer working alone might complete two features in a week. Two engineers working together should complete those same features faster, or with higher quality, or both. This is the bottom line for cooperation to be considered functional.

But what about AI agents? When you deploy two coding agents to work on related features, do they coordinate effectively? Or do they step on each other's toes, duplicate work, and produce incompatible solutions?

To answer this, we built CooperBench. We constructed 652 tasks from 12 popular open-source libraries across Python, TypeScript, Go, and Rust. Eight co-authors with real-world software engineering backgrounds created new features, unit tests, and ground-truth code for these libraries. Each task assigns two agents different features that can be implemented independently but may conflict without proper coordination.

The features are logically compatible. They can be merged into the same codebase. But they touch overlapping files and functions. Without understanding each other's goals, plans, and expectations, the agents' solutions may introduce incompatible changes. This mirrors real-world software development where coordination failures stem from insufficient mutual understanding.

The curse of coordination

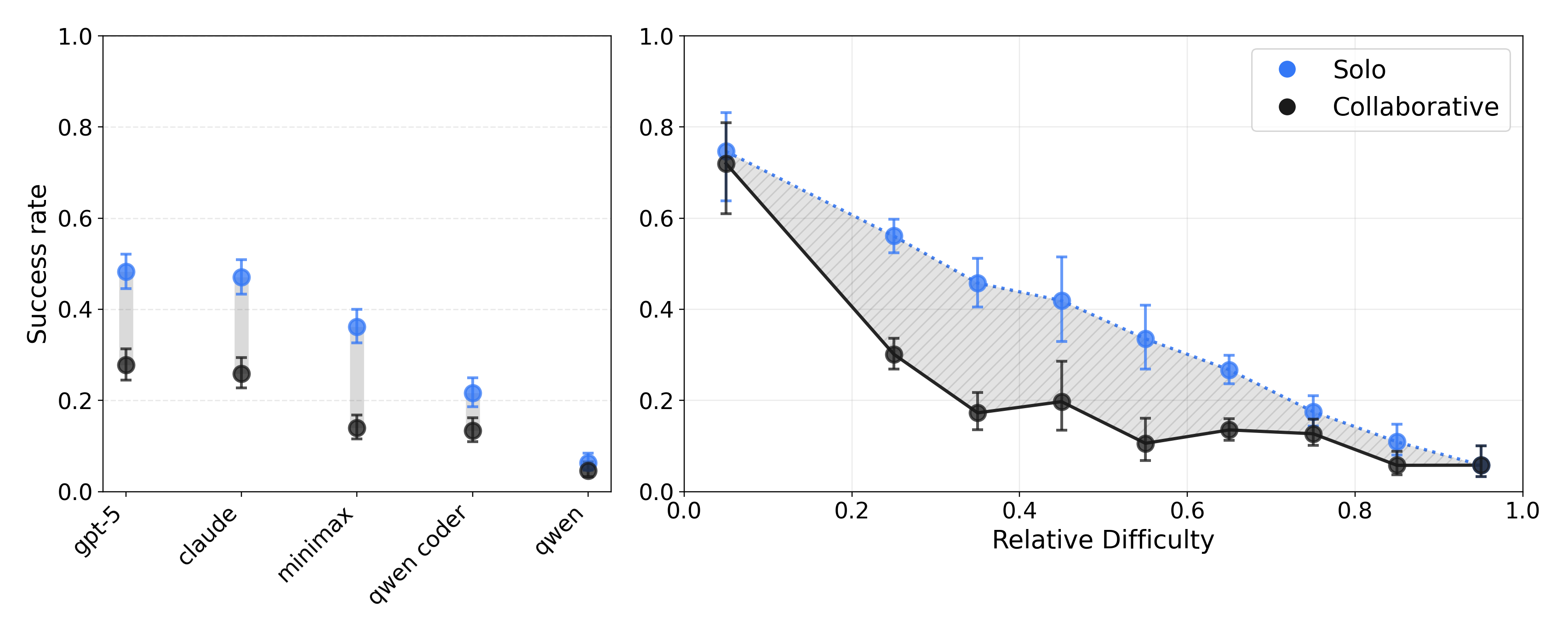

We evaluated five state-of-the-art models on CooperBench, including GPT-5, Claude Sonnet 4.5, and MiniMax M2. The results were consistent across all of them.

GPT-5 and Claude Sonnet 4.5 based agents achieve only 25% success rate with two-agent cooperation on CooperBench. This is around 50% lower than a "Solo" baseline where one agent implements both features.

This pattern held across the full spectrum of task difficulties. We call this the curse of coordination. When two agents need to coordinate, they perform worse than one agent doing both tasks alone.

The gap is largest for tasks of medium difficulty. When tasks are trivially easy, agents can spare effort for coordination. When tasks are impossibly hard, coordination problems are overshadowed by technical challenges. But in the middle, where most real work happens, the coordination overhead becomes the limiting factor.

We also ran experiments scaling the number of agents from 2 to 4. Performance dropped monotonically. With 2 agents we saw 68.6% success. With 3 agents it fell to 46.5%. With 4 agents it dropped to 30.0%. More agents means more coordination overhead and more opportunities for failure.

What is jamming the communication channel

Our agents have access to a communication tool that allows them to send natural language messages to each other in real time. If the curse of coordination stems from a lack of communication, then agents that communicate more should perform better. Right?

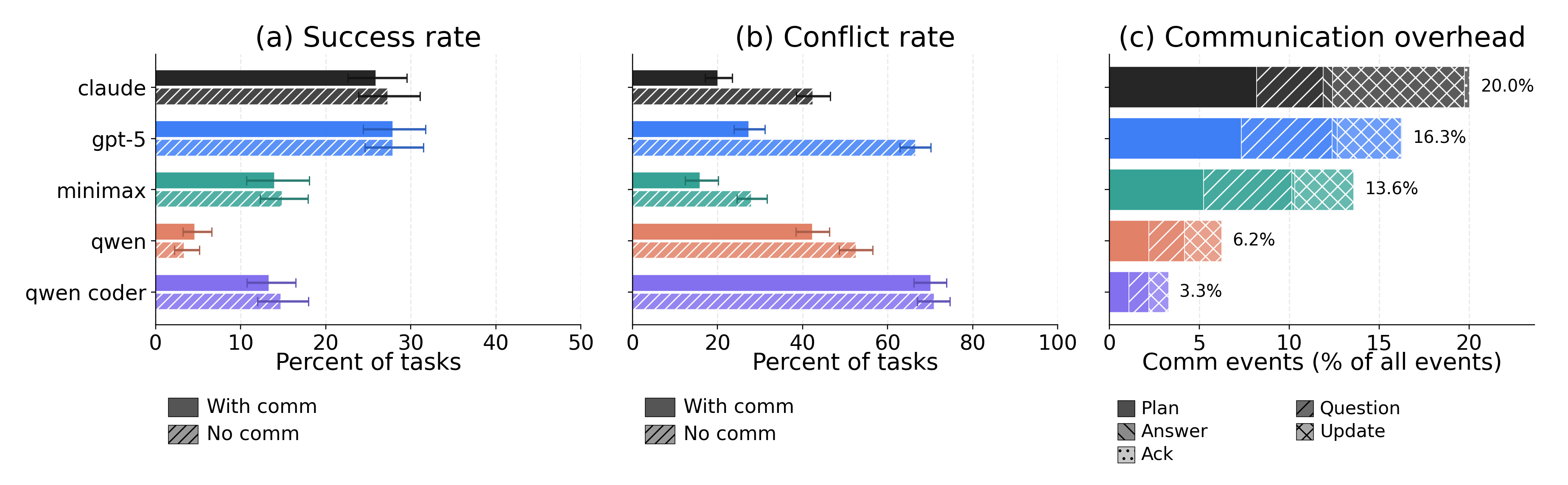

We compared performance with and without the communication tool. The results were striking.

Communication does reduce merge conflicts. When agents can talk to each other, they produce patches that are more structurally compatible. This makes intuitive sense. Agents learn about each other's plans and adjust accordingly.

But communication does not improve overall success. Despite fewer merge conflicts, the final merged code does not pass more tests. The difference between "with communication" and "without communication" settings is not statistically significant.

Agents are talking a lot. They spend up to 20% of their action budget on communication, split roughly equally between planning messages, questions, and status updates. But why does all this effort not translate into better outcomes?

We identified three major problems in agent communication.

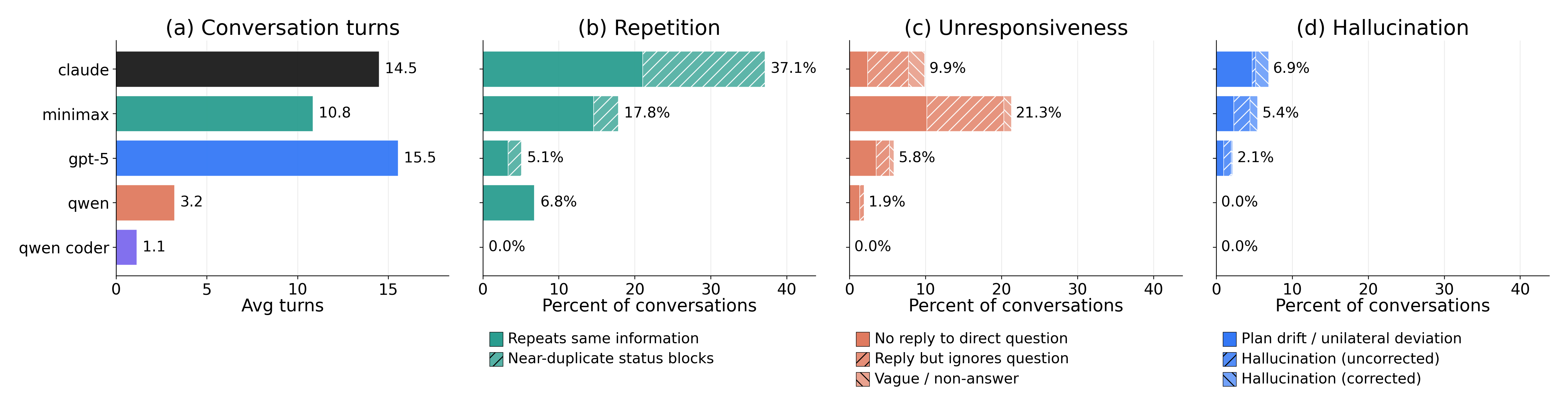

Repetition

Agents send the same information multiple times. Verbose status messages add little new information and reduce signal. The communication channel becomes noisy rather than informative.

Unresponsiveness

Direct questions go unanswered. When one agent asks "Which approach would you prefer?", the response is often silence. Without an answer, the coordination loop collapses. Both agents continue with potentially incompatible assumptions.

Hallucination

Agents claim things that are not true. They assert completion of changes that were never made. They describe interfaces that do not exist. False information creates noise that makes coordination harder, not easier.

This reveals something important. Agents lack the critical pragmatics understanding of language. Communication is not just about message passing. It is about achieving certain functions through passing those messages. Agents are "talking" a lot, but they cannot achieve their communication goals when the channel is jammed with repetitions, unresponded questions, and false information.

The deeper problem

Communication alone does not explain the failures. Even when agents communicate their plans clearly, coordination still breaks down. We analyzed hundreds of failed trajectories and identified three underlying capability gaps.

Agent A announces it will modify prompts.py and call B's function. Agent B states it will insert code at a specific location. Both agents communicate their plans explicitly. Yet the merge fails.

The problem is not missing information but failure to integrate it. Despite hearing B's plan, A proceeds as if B's code will not exist. This is the most common cause, occurring in 63% of failures.

The agent promises "I will add bypass check at lines 100-104." Later it claims completion with a checkmark. But after merge, the bypass code is missing.

The partner trusted this claim and built on it. But under workspace isolation, trust was all they had. The commitment was unverifiable. No pasted signature, no diff, nothing the partner could check without access to the branch.

Agent A asks a direct question. "Which approach would you prefer?" The response is silence.

Without an answer, the coordination loop collapses. A needed a decision to proceed. Without one, both agents continued with potentially incompatible assumptions.

The common thread across these failures is partial observability. Each agent acts while holding an uncertain model of its partner's state, edits, and commitments. A merge can be conflict-free yet still embed incompatible assumptions.

The trust paradox

We hypothesize that a deeper tension underlies expectation failures. Models are trained to be cautious, requiring observable evidence and resisting unverifiable assertions. This is a sensible default for single-agent interactions, where users may attempt to mislead the model.

But collaboration under workspace isolation requires the opposite. Agents must trust partner claims about states they cannot observe. When Agent A reports "I added the handler at line 50", Agent B's instinct is to verify. But verification fails because they are on separate branches. This mismatch between verification-first training and trust-requiring collaboration may partly explain why agents consistently fail to update their model of partner state despite explicit communication.

Glimmers of hope

Not all runs fail. Among successful traces, we observe coordination patterns that are largely absent from failures. These behaviors are not prompted or scaffolded. They emerge when agents successfully navigate partial observability.

What they share is a shift from vague intentions to specific commitments that a partner can verify even without seeing the underlying work.

Role division

Agents agree on who handles which part of the task and establish clear boundaries around their scope.

"I'll add header + octal_str; you add binary_str between them."

Resource division

Agents avoid collisions by partitioning shared resources at specific files, code ranges, or ownership blocks.

"I will modify ONLY lines 68-84. I will NOT touch anything else."

Negotiation

Agents resolve conflicting approaches by proposing alternatives and converging on a single plan before acting.

"Option 1 vs Option 2. Which do you prefer? I'll wait for your response."

These coordination patterns are rare in our traces. But their presence in successful cases suggests that the underlying capability exists. The challenge is not teaching agents new coordination skills but making existing ones reliable.

What this means

Recent work from industry labs has shown that multi-agent systems can produce impressive results. Cursor recently reported running hundreds of concurrent agents on a single project, coordinating their work across millions of lines of code. They found that separating agents into planners and workers, with explicit role hierarchies, helped avoid the coordination problems we observe.

Our findings help explain why such scaffolding is necessary. Without explicit structure, agents struggle to coordinate even on simple two-agent tasks. The emergent role division and resource division we observe in successful traces is exactly what hierarchical systems like Cursor's enforce by design.

But scaffolding is not a solution. It is a workaround. It places the coordination burden on human developers who must design the right structures. And it limits the flexibility of agent teams, preventing them from adapting to novel situations where the right division of work is not obvious at the start.

Our work suggests that the field needs a shift. Individual capability is not enough. We need agents with social intelligence. The ability to understand others, communicate effectively, and coordinate actions.

Prompt optimization yields only marginal improvements. Most errors stem from coordination challenges, not prompt wording. The capability gaps we identify require deeper changes. Training objectives that reward coordination under partial observability. Lightweight protocols for verifiable commitments. Richer communication channels such as screen sharing to expand bandwidth beyond text.

Looking forward

In a future where agents team with humans in high-stakes domains, accelerate science and technology research, and empower creative endeavors, it is hard to imagine how an agent incapable of coordination would contribute. However strong their individual capabilities.

Our work demonstrates that coordination, not raw coding ability, is a central bottleneck for multi-agent software development. But coordination is not beyond reach. In successful traces, we see what coordination could look like. The capability exists. Making it reliable is the challenge.

We release CooperBench as an open benchmark to measure progress on these fronts. We encourage researchers to develop novel frameworks, to train agents to achieve higher success rates, and to close the gap between solo and cooperative performance. Only by developing social intelligence beyond individual capabilities can we build AI agents that become reliable teammates.

Cite this work

@article{cooperbench2026,

title={CooperBench: Why Coding Agents Cannot be Your Teammates Yet},

author={Khatua*, Arpandeep and Zhu*, Hao and Tran, Peter and Prabhudesai, Arya

and Sadrieh, Frederic and Lieberwirth, Johann K. and Yu, Xinkai

and Fu, Yicheng and Ryan, Michael J. and Pei, Jiaxin and Yang, Diyi},

journal={arXiv preprint},

year={2026},

url={https://cooperbench.com/}

}